All the talk about J. K. Rowling's enormously popular kids' books got me thinking that I hadn't read a book for fun in a very long time. I've been reading some of the books that "defined" the "Appalachian people," like John Fox Jr.'s The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come and Emma Bell Miles' stories and fictionalized essays, and James Dickey's Deliverance, and I've been dutifully reading fictionalized accounts of local history by Pocahontas County natives G.D. McNeill (father of nationally recognized poet Louise McNeill) and W. E. Blackhurst. Our Pocahontas County authors seem to have admired Fox's prose, and emulated him by writing some of the most wretched dialogue ever to come off a vanity press. Add to that my distance-education research reading (much use of buzzwords like "user-defined," "multiple perspectives," "blended learning") and you have the roots of my reading disphoria.

I already know Harry Potter's not the answer for me. Last fall, I sat in a middle-school library waiting for my students, picked up the first Rowling book, and put it down again after 30 pages. Unlike Harold (Harry?) Bloom, I don't think Harry Potter prefigures the end of Western Civilization, but it wasn't fun for me. I'll wait for the Cliff Notes. My local library has plenty of reading about Appalachia and Pocahontas County, and I am grateful, but those books are how I came to this dreary state of mind in the first place. The library's fiction collection is skewed toward recent best-sellers in genres I don't care for, so my next move was to search my shelves for novels I hadn't already read that might be, somehow, "fun."

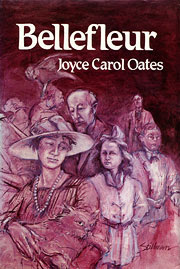

Usually, when I'm feeling grumpy, I reread old favorites (Austen, Dickens and Conrad, or perhaps John D. MacDonald or Tony Hillerman), but part of what I've been missing is that "What happens next?" feeling J. K. Rowling has been so concerned to preserve from "spoilers." I pulled out three books I thought might do the trick: E. R. Eddison's The Mezentian Gate, Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! and Joyce Carol Oates' Bellefleur. I was surprised to find my unread novel collection so heavily skewed toward the Gothic.

First I opened E. R. Eddison's The Mezentian Gate. I found I had started it before and didn't finish it. The bookmark was a "STOP JOB" card, and the book was a Ballantine paperback with cover art by the same artist used for their Lord of the Rings edition. After I got over this seventies flashback, I discovered why I'd left off at page 73. Eddison's stylistic inspiration seems to be Gothic classics like The Castle of Otranto and The Duchess of Malfi, but he doesn't match their action-packed pace. Also, the made-up names make me giggle every time he introduces a new character. Rhodanthe of Upmire, daughter of Sidonius Parry.

I turned to Bellefleur next. I admire Joyce Carol Oates, but I tend to approach her novels the way I approach having blood drawn. It's a worthwhile endevour, but not usually fun. I was surprised to find that, although Bellefleur has its share of murders, rapes, agonies, and tortures, there is also mystery, magic, and mythology, adding a playful element where Oates winks at us. It's fiction, not a documentary.

On Celestial Timepiece, a Joyce Carol Oates page named after a quilt design in Bellefleur, I found an interesting essay by Oates from her "Preface to The [Franklin Library] First Edition" of Bellefleur:

The imaginative construction of a 'Gothic' novel involves the systematic transposition of realistic psychological and emotional experiences into 'Gothic' elements. We all experience mirrors that distort, we all age at different speeds, we have known people who want to suck our life's blood from us, like vampires; we feel haunted by the dead--if not precisely by the dead then by thoughts of them. We are forced at certain alarming periods in our lives not only to discover that other people are mysterious--and will remain mysterious--but that we ourselves, our motives, our passions, even our logic, are profoundly mysterious....If Gothicism has the power to move us (and it certainly has the power to fascinate the novelist) it is only because its roots are in psychological realism. Much of Bellefleur is a diary of my own life, and the lives of people I have known....

Bellefleur is more than a Gothic, of course, and it would be disingenuous of me to suggest otherwise. It is also a critique of America; but it is in the service of a vision of America that stresses, for all its pessimism, the ultimate freedom of the individual. One by one the Bellefleur children free themselves of their family's curse (or blessing); one by one they disappear into America, to define themselves for themselves. The castle is destroyed, the Bellefleur children live. Theirs is the privilege of youth; and the 'America' of my imagination, despite the incursions of recent decades, is a nation still characterized by youth. Our past may weigh heavily upon us but it cannot contain us, let alone shape our future. America is a tale still being told--in many voices--and nowhere near its conclusion.

So I can still enjoy fiction. On to Faulkner!

No comments:

Post a Comment